This was the time of our child custody travels between home in town with my mom and Javan and my dad's, from Arcata to Southern Humboldt, from Victorian landscaped houses, through redwoods, to the madrone, fir, spruce Eel River wilds in that pot growing capital of the country.

That summer, my father had demanded that my sister and I stay with him for a few months in his one-room cabin with his girlfriend out in the woods. It was a compromise. He had come for custody. But my mom told him she would rip his lawyer’s nuts off and feed them to him. “It’s a woman,” Dad said.

We had agreed to the summer.

It was 1985.

At home with Mom and Javan, I was a jock, a brain, a loner, and, secretly, a rebel. I rode my bike to see Out of Africa, emerging into the still light summer evening, with Meryl Streep reading “An Athlete Dying Young” over her lover’s grave sounding in my heart with the image of the African new moon, laying on its back. Sometimes I went to the movies with my mom and sister. Often, we rented a VCR—a hulking thing that came in a plastic suitcase. We picked the videos off the shelves at the store, stayed up late, splurging, woke up early, splurged more.

At first, I took my fashion from movies, cutting off the collars of dress shirts and bringing home finds from the thrift stores. My mom and Javan spent hours with me and my sister, in the discount sections, looking for patterns, colors, shoulder pads. Broad and big we wanted to be, our bodies lost in layers, like the hero of The Legend of Billie Jean. Eventually, I settled into 501s, which I sewed tight around my calves, with sneakers, and a white shirt under my letterman jacket.

Once my mom borrowed the sneakers I played basketball in. She said, “now I see why you strut like you do!” and emulated my jaunty jock walk, my tiger prowl. One day in practice, I didn't have my shoes. The star of our team gave me a pair of her old Adidas, which were ripped across the toe. I wore them for the rest of high school. She was the girl I looked for as she cut through the key. She would widen her dark blue eyes and flash her hands to her chest when she was ready for the pass.

At least once, she wore my letterman jacket. The girls’ jackets had wool sleeves. I wanted the leather ones. Shorthaired tomboy, I was still flat-chested. The guy at the store suggested a roomier fit, for when I “filled out.” My mom made a shocked face. “He thought I was a boy,” I whispered to her on our way out the door.

My stepfather, Javan, was a minister. He got me a key to the nearby Presbyterian Church, which had a wood-floored room with a basketball hoop where I could practice. There were rolling mirrors there. I supposed the room was also used for ballet classes. The sun would come in the windows in the afternoon as I played alone. I developed a sweet hook shot I would never use in a game, leaping up arrogantly like a dancer, with a sweep of my right arm over my shoulder as I turned my gaze to the net, spinning with a snap.

Once, when the star came to play with me there, I did use that hook shot against her boyfriend, a lanky stoner kid.

From this town with movie theater, basketball court, and thrift stores, my sister and I would get on the Greyhound bus to travel the two hours plus southward to the Redway stop where my dad and his girlfriend Ruthanne would pick us up. There was only room for us in the back of the pick-up.

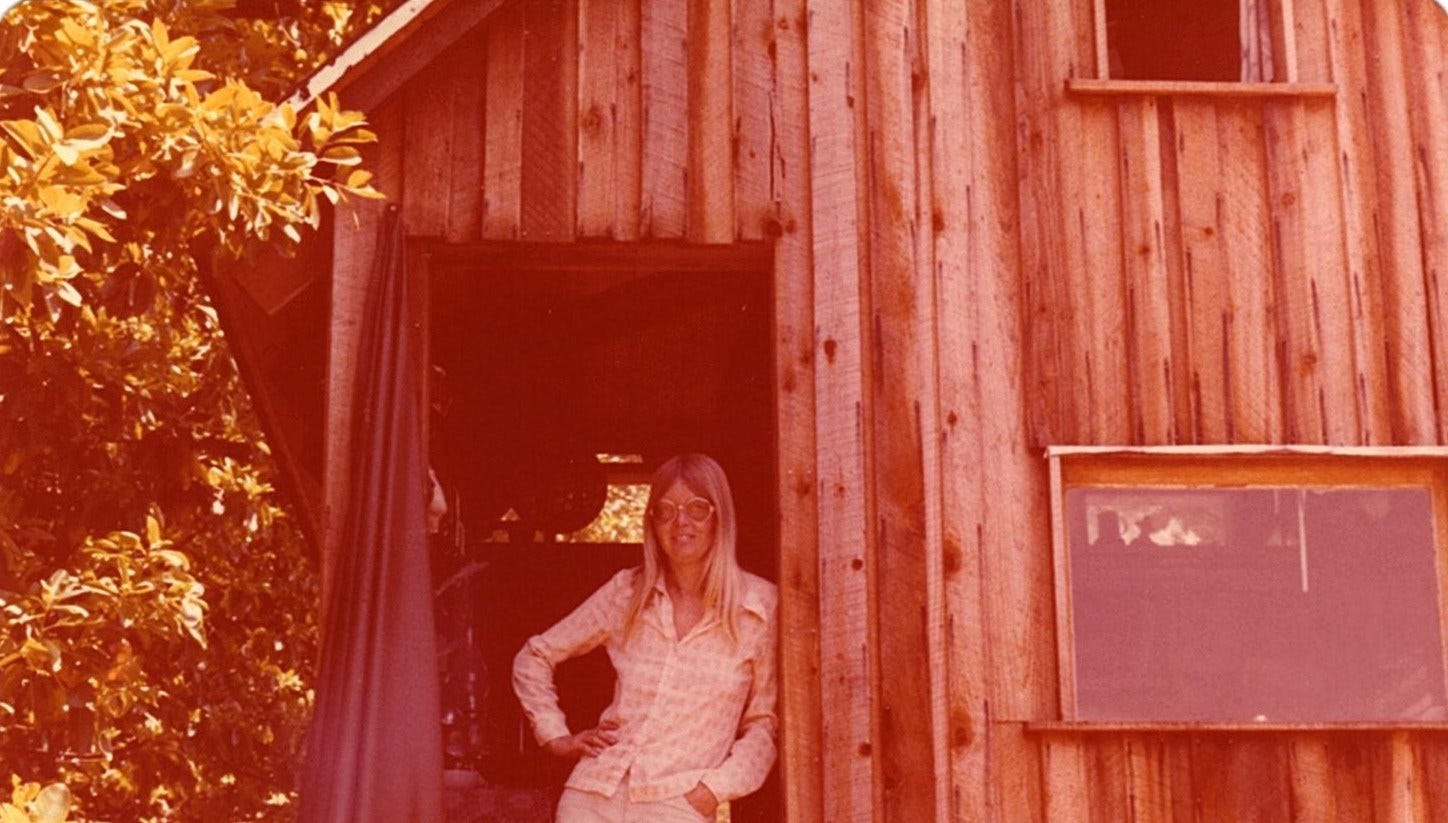

The drive up to Ruthanne’s cabin seemed to be at least an hour, winding up from the Eel River Valley and the 101. There was always the decision to not take the turn to Whitethorn, where Ruthanne’s son Donovan lived with his dad Vane over a mechanic’s shop. We would go up the hairpin turns from that intersection, then swerve suddenly into the quiet of dust, onto a network of dirt roads. In his rusty, turquoise, hand-me-down Datsun pickup, with its jerky idol and loose shocks, we would rattle along at a young father's breakneck speed, swerving to find purchase on parts of the road less potholed and wash boarded and grooved by drivers he complained went too fast.

Ruthanne’s was a 12-by-12 cabin, lit by candles and kerosene, heated by wood. I remember the smell of the secondhand paperbacks that insulated it. When we first showed up, dad took us out to pick huckleberries. We watched him cursing over the whole wheat pie crust. It was a summer my dad had quit drinking. We all binged on Calistoga’s, bubbly water that didn't taste nearly as good as La Croix. Green salsa and corn chips. I remember greasy fingertips from black cast iron pan roast chicken, potatoes, and vegetables cooked in the wood stove in that tiny kitchen that had to be cleaned up immediately, where dad taught us the kitchen dance: “you take it out, you put it back.”

There was the vegetable garden and the outdoor shower that we heated by coiling black pipe on a sunny hillside so, when the tank was full, you could have a brief late morning shower, looking out into the squash and tomatoes. Here, as at the River House, as at Greenwood Drive, our dad built us a treehouse. I helped carry the wood and the nails and the tools across the bluff, where the pipe was coiled, to what he had identified, in anticipation of our stay, as the perfect tree. He built great outhouses too.

There was the Shit, Fuck, Piss Ranch that my dad walked us to one day, with its ghostly western movie sets, all funded by Humboldt bud. I imagined utopian escapes of a bygone era. We had grown up seeing the Camp raids on TV, soldiers setting fire to peoples’ crops. Dad reassured us he knew the guy who owned this place. But there was also the noisy generator at the pot farm down the hill, warnings not to hike across strangers’ land, discussions of how cocaine and guns had changed the culture.

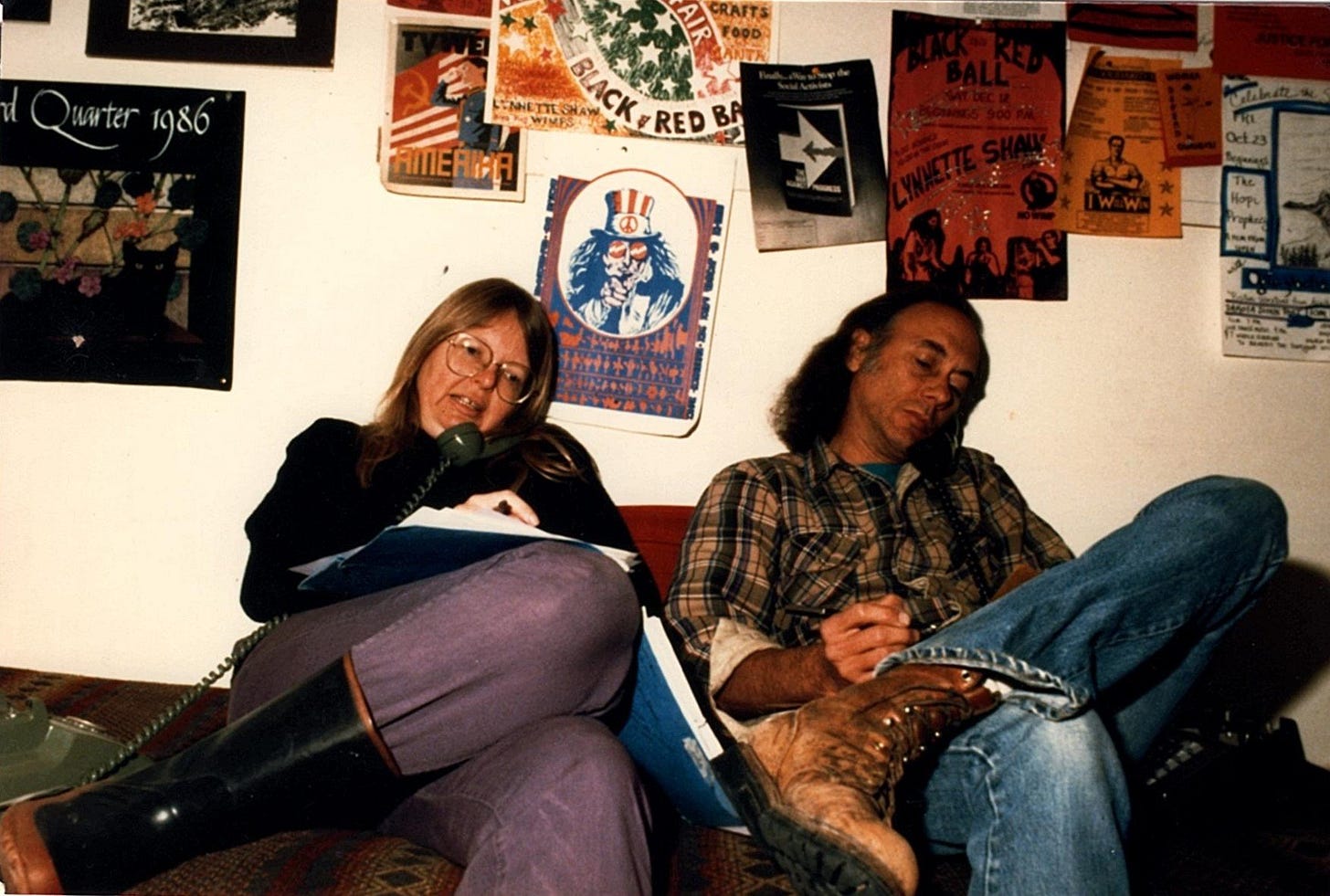

I had planned to use the endless empty time to become ambidextrous and practiced writing left-handed for hours on the porch. But then I said something that caused my father to slam in and then out of the cabin with a cassette recorder and a box full of tapes by journalists of the Iran-Contra scandal. “Listen to this,” he snarled. So, I did.

We couldn't get clean as there was a water shortage. When we went into town for a grocery run, my sister and I waited in the back of the truck in the parking lot. Teenagers were joking around in front of the store, kids my age I feared would see us. Madonna’s newest song “Get into the Groove” blared across the lot.

Only when I'm dancing can I feel this free

At night, I lock the doors, where no one else can see

I'm tired of dancing here all by myself

Tonight, I want to dance with someone else

There were the hours and hours in the car and at meetings or sitting around on those hot summer days while he worked. We read through the books that insulated Ruthanne’s cabin. We played cards in the trailer he had brought to Ruthanne’s land for us to stay in that summer, the very trailer we had lived in when we first moved to Humboldt County in 1977 to stay for a summer on Brannen Mountain. Holly and I usually played cards all summer, one game a summer. War, Crazy 8s, Gin Rummy, then Hearts. But this was the summer of Parcheesi, or was it Hearts? Was this the time my little sister shot the moon and Dad got pissed?

There wasn't a lot of engaging. We knew it mattered to him to have us there. My sister had pretty much had enough of that. I agreed. We were bored. We were teenagers. I should be practicing. She missed her friends. So, we determined one day to tell him we wanted to go home to our mom.

He had been ignoring us for weeks, we had not expected him to cry. Nor did we expect to face his arguments and accusations. We did so, stoically, each of us in our trailer couch, our feet up on the walls.

We won.

Back on the Greyhound we went, northbound to Arcata, to our mom and our town life.

For other essays on my Generation X experiences:

I really enjoyed this deep dive back into the past, Heather. I love articles like this and I'm continously blown away by your masterful use of words!

The summer of 1985. Your penchant for detailed memories along with the easy flow of your sentences transports us, your readers, back to this time with you. Housed in the experience of being an 80’s teenager, riding the ripples of adult drama, filling out the contours of our own adult personalities and discovering the aloneness of our human experience even when living in cramped conditions. I met you a few years down the road from this age, me straight from suburbia, you still smelling of river water and forest green. I love your courage to return and revisit your younger self to help inform the who you are today - I greatly enjoyed hopping into the back of the pick up truck and joining you on the journey to the cabin and felt the relief/sadness of the Greyhound bus returning you home