One night at the observatory, Lyudmila told Manny about Venus. All of it. Tamara and Bernice and the red bird. And the phosphine gas from the 1978 Pioneer Venus probe, the alien life it suggested.

Manny walked into Lyudmila’s office the day she learned that Tamara had died.

It was 2001.

“Manny Zaki.”

Lyudmila looked up at the tall, lithe person offering their hand across the desk. She had just placed the receiver into the cradle and in a practiced motion, reached down, opened her bottom drawer, and pulled one of the cheap highball glasses she kept there. She put the glass on the desk and half stood to shake Manny’s hand. It was warm, smooth, golden.

“Hello Manny,” she said. “Will you have a drink with me? I have just had some sad news.”

“Many,” the name came out, translation across two accents.

“Egypt,” Manny said, anticipating the usual question.

“Pardon me?” Lyudmila had again bent to her bottom right drawer, for the second glass and then the fifth of vodka. She looked over her shoulder at Manny with her dark blue eyes and smiled her half smile.

This half smile, the attempt at humor in the deep, cool, eyes, all struck Manny with sorrow.

Manny sat down. Lyudmila poured.

“No thank you, but please, go ahead,” said Manny.

“Many Zaki,” Lyudmila repeated, pushing a glass towards Manny anyway. “You are one of my new grads. I remember. Your name, Zaki. It means ‘pious.’ Odd name for a scientist.”

“No better way to know god than in looking at the stars.”

“You know Many? You are so right.” Lyudmila huffed out her nose, amused. “Tell me about yourself.”

Manny leaned back in their chair and began to tell Lyudmila about their dreams for their graduate study in astronomy. They reached up to their hair in a practiced fidget and let the knot loose, then smoothed and twisted and knotted as they talked. Lyudmila was supremely easy to talk to.

Then Manny stopped talking. They looked into Lyudmila’s dark stare. That half smile again. Damn.

“You have amazing hair,” said Lyudmila. She had sat in her heartache as Manny talked, having swallowed her drink quickly. Her vagus nerve she knew was responding to the organs of her body, to the sounds to her ears, the sad news that had come over the line, the low, clear sound of Manny’s voice, to the sight before her, the clear liquid, the person at her desk. Her eyes burned. Her grief did something to her throat. A lump. To her chest. It made her feel knifed.

The vodka burned down her. She poured another to sip. Though she wanted oblivion. She waited. Made herself suffer. She was good at that.

Her vagus nerve put butterflies in her stomach too. This gorgeous young person reminded her of youth, of her own earliest visions. And of something ancient too, something that went across the unknown, that zapped and lit up the electric connections.

When Manny again shook her hand and said goodbye. Lyudmila took that long, fast drink she had wanted. She also emptied the glass Manny had left untouched.

Oblivion did not come. It had not come for many years.

That was the beginning.

Lyudmila had defected in 1979. She and Niki were invited to Hawaii for a meeting of astronomers engaged with sending probes and flybys towards Venus. The Americans’ 1978 Pioneer Venus had collected data the Soviets wanted. She was to use her considerable charms to win access to it from one of the American scientists there.

She got the information. She and Niki conferred beneath the starry sky as they swam in the warm ocean.

“I don’t think they saw it,” she said. “I don’t believe they know what they have Niki. But it is a sign of life.”

Nikolai had returned home to their children. Lyudmila would not see them again for more than two decades, after the eastern bloc finally opened.

There had always been in her that need to suffer. The world as it was designed caused this.

She stowed away on a ship. Her American scientist had arranged everything with his connections. Now, here she was, ultimately, a disappointment to the Americans, at a small public university in Northern Arizona. But free. Free to suffer. Free to look at the heavens. Free to yearn for Tamara. Niki. The children. All out of reach. All tied securely to her by silk, to the network, her nervous system.

In the morning she woke shocked at her heartcrimes. It felt like the fist of muscle in her chest was bound up. Several times a day, some object, a perfume, a thought, a doubt would yank one of those silk cords.

Isolated in her convictions, she suffered.

Yet, she was not one to wear armor. Or to dread pain. Now Manny, dipping in her door. Lyudmila’s stomach lifting suddenly at the sight of a figure in the beige halls, far ahead, turning a corner. A familiar gait.

Ridiculous, Lyudmila chided herself. But it made her smile too.

They worked well together. Manny was quick and quietly brilliant, making leaps and connections across gaps Lyudmila had become resigned to never bridging, had not known she needed to.

For Lyudmila, these were years full of joy. Tortured by desire, but happy. Sometimes she felt the red bird blooming in her chest, a whole new world to greet each dawn for. She was too old now for acting on such thoughts she told herself.

She rushed to work, balancing her creamy, spiked coffee on the dashboard of her Subi, taking sips between lights in the navy pre-pink morning, eager for her calculations after hours the night before behind the telescopes.

Everyday she knew that soon she would look up from her desk and see Manny leaning against her door jamb, holding a sheaf of papers, a pencil in their knotted hair to pull out and jot notes. The clean smell of the tumble of that dark, straight, shining hair. Manny’s gesture to push it back behind their ear. How it would fall again, lit with auburn from Lyudmila’s desk lamp.

One night at the observatory, Lyudmila told Manny about Venus. All of it. Tamara and Bernice and the red bird. And the phosphine gas from the 1978 Pioneer Venus probe, the alien life it suggested.

“I want to show you something,” she said. She entered some coordinates into the telescope consol and, as they waited for it to move there, she told Manny the whole story.

It was 2008.

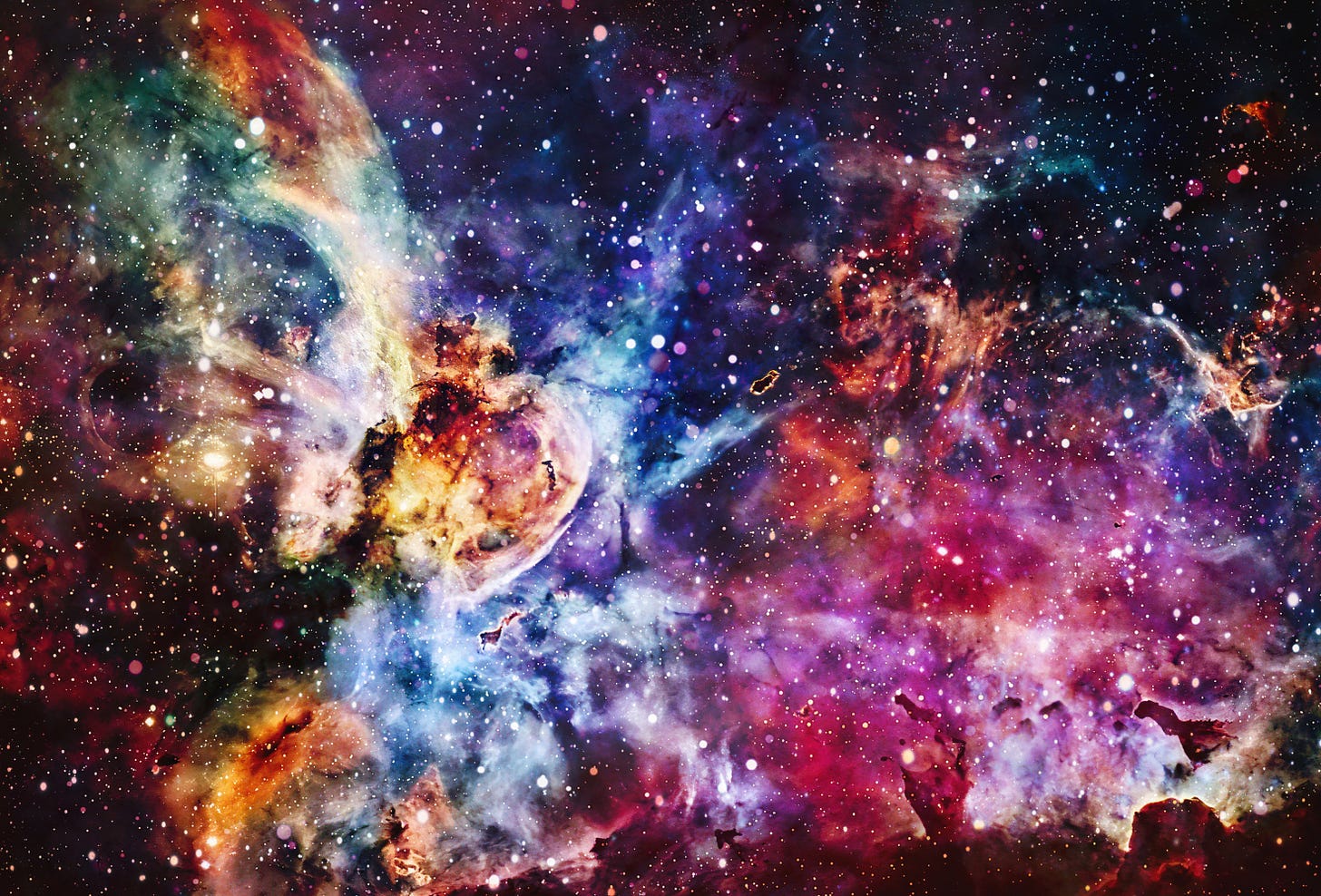

Listening, laying in the chair beneath the lens, Manny realized they were holding their breath as Lyudmila talked. Lyudmila was not looking at Manny, just watching the roof as the great scope whined and whirred its slow way towards a spot just beyond Venus, to the gate Lyudmila’s calculations said would open there.

Manny was looking at Lyudmila out of the corner of their eye, indulging longer and longer moments to rest their cheekbone to the chairback in order to stare directly at their teacher as she spoke. This was the side of Lyudmila that smiled, the half-smile that began gloriously at the eyes, deep laugh lines that were so beautiful—

Lyudmila was talking and shaking her head side to side over her feeling for Tamara and at how brazen they had all been 38 years ago…38 years ago, the year Manny was born. As she shook her head, Lyudmila caught a glimpse of Manny from the corner of her eye. Manny was staring at her, brazenly now.

Lyudmila stopped talking.

With a small laugh of recognition and happiness, Lyudmila stared back. It was quiet for a long time.

“I have been meaning to ask you,” Lyudmila said. “How is it that you don’t drink?”

THE NEXT CHAPTER:

Saving Power, 2022

The woman, Atalanta, bent over to look closely, took her phone from her pocket and squatted, shifting, zooming, circling, making art, capturing for release—on the web perhaps. In explorations of the web that became the Wiki, the Great Mycelium encountered a beautiful, sad essay. “All saving power must be of a higher essence than what is endangered, thou…

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

This story came from a tarot reading.

This is a chapter in a larger project I am revising and posting here.